A World of Books and Children

Search and enjoy 8 years of posts chock-filled with ideas from It’s OK Not to Share and beyond.

I've never been a fan of coloring books. As a child I don't remember liking them, and as an adult they always seemed to me to stifle imagination. Boy, I was wrong. I can tell I was wrong because a child showed me.

As parents, we all start out with definite opinions about this or that. When it comes to changing your mind, I say let the child lead you.

My 5-year-old loves coloring. In his hands, a coloring book sparks his imagination. He can't yet read, so coloring is the way he interacts with books and topics that excite him. Right now he adores stories about the American Revolution and coloring intricate pictures of his heroes like knights and firefighters. As he colors, he brings the ideas alive from the page. Then he acts out the story. There's no question coloring books stimulate him and meet a deep need.

It took us a while to figure this out. My aversion to coloring books at first blocked me from seeing his need. I had no intention of buying a coloring book, but he kept showing us his need to color. He colored his blanket, his wall, scraps of paper, his favorite library book. He longed to color every storybook he owned. Finally, I saw it. So I changed my mind.

I've seen this happen over and over again to parents who swear they will never let their child engage in certain play. "I was one of those mothers who was never going to let her child play with toy weapons," parents repeatedly tell me. "Tyler changed my mind. And by the time my third child came along, we had quite a collection." Or "I didn't want to raise my girl to dress in pink and play with fairies. But it's so strong in her."

It's OK to change your mind. Healthy parents change their minds all along the way. The key is to change your mind for good reasons.

All behavior has meaning. A child deserves to have his/ her play needs met. Change your mind or methods to fit the need, whether it's getting play clothes for mud digging, allowing stick swords, accepting fairies in your home, or even (gasp) buying a coloring book.

So go ahead and change your mind. Let the child lead you.

What have YOU changed your mind about? What types of play does your child like that bothers you?

It's the season when families converge for the holidays. In honor of Thanksgiving this week, here are some thoughts on helping young children navigate the well-meaning hugs and kisses of relations.

The basic premise: it's OK NOT to kiss Grandma.

Or Grandpa, or Aunt Rosie, or any of the extended cousins, uncles, great-aunts, neighbors and guests.

Unless relatives are regularly part of a young child's life, remember these people are strangers. Has it been six months since you've seen Uncle Claude and Aunt Sophie? A year? Two years? That could very well be half the child's life. Chances are, your child feels more comfortable with the babysitter down the street. Even if your child had a terrific time the last time they were together, this family member is essentially a stranger now to your young child. It's important to respect that, acknowledge fears, and don't force affection.

It's ironic, isn't it? Most families spend a good portion of the year telling their kids not to talk to strangers. Then at the holidays we expect children to hug these "strangers" and let themselves be petted and kissed.

Young kids are often scared of people who are new or different. They might be worried about people with beards, people with wrinkly skin, people who walk with a cane or use a motorized wheelchair. They might not know what to say, or be put off when their slightly-deaf grandparents can't hear them properly.

Some tips to help everyone feel comfortable:

Go slowly Don't insist on instant hugs and kisses when greeting family. Model your own trust and affection, but allow your child to observe, warm up, and take his time getting to know them.

Respect the right not to be touched Children should have privacy over their own bodies. They have the right to give and accept hugs or not. If a child doesn't want to touch someone, or be touched, that's just fine. In fact, it's healthy. Your child is setting boundaries on her body.

Set expectations Talk about it ahead of time. Acknowledge that you haven't seen Grandma or Grandpa in a long time. Explain what you expect: "There'll be a lot of people coming to our house tomorrow. It's nice to say 'hello' when you meet people." Also explain what your child can expect. "Nana's excited to see you. She likes to kiss people when she sees them." Don't forget to warn the grandparents! "Nathan doesn't like hugs right away. He's excited to see you again, but remember, it's been a long time. The best way to make friends is to read him a story."

Focus on modeling, not performing When guests arrive, don't force young kids to perform polite greetings. They may clam up or hide behind your legs. Let your ideas of manners for greetings and goodbyes go. Older kids can be expected to say hello, goodbye and thank you-for-coming, but many young kids pick it up best through observation. Time is your friend here. Respecting feelings is more important and will allow a stronger relationship to develop over time.

Offer tips If Grandma uses a walker or Grandpa's hard of hearing, talk about it. Answer basic questions and give your child tips for success. "Grandpa can't hear well. Stand right next to his chair and say it again in a big voice."

Revive memories Tell stories to reconnect your child to the family members they're about to meet. Even if they're too young to remember the last visit clearly, you can still say "Grandpa rocked you in the rocking chair when you were a baby. See here's a picture." Knowing their connection helps establish trust and a new bond.

Of course, the opposite may become a problem, too. You may have to rescue Aunt Sophie or Grandpa from an onslaught of excited squirmy hugs from your child. Grown-ups have a right to say no and protect their bodies, too.

Has this ever been a problem in your family? Do you remember what it was like to meet extended relatives at family gatherings? What do you think accepting forced affection teaches kids?

We know kids need time to play, but how much time? As much as possible. But what's key when we talk about play time is protecting BLOCKS of time.

When I visit many "play-based" programs to observe, I see actual play - free, unstructured, child-initiated play - squeezed in between multiple structured activities. Sometimes play is only given 15 minutes. A sort of "in between" time while the adult sets up the next structured activity.

Other programs, especially ones based in elementary schools, are chock full of transitions. Children may get play time, but it's constantly interrupted by scheduled appointments such as gym, art, music, snack, language study, circle of friends, etc. These special classes may be worthy, but they also break up the young child's day.

Children need blocks of time to play. Researchers have found that blocks of 1-2 hours or more are ideal. Studies by Dr. James Christie and Dr. Franics Wardle show that shorter play periods (less than 30 minutes) reduce the complexity and maturity of kids' play. Kids will still play in short, squeezed bits, but they drop sophisticated play. Short play is still good, but when the sophistication level drops play loses many of its benefits.

Teachers at the School for Young Children have found that preschool kids need at least 45 minutes to get into really good play. And once deep play has started, kids need more time, well beyond that 45 minutes, to expand and develop that play. The game needs time to play out.

I recently visited a cooperative preschool in Ann Arbor. Their daily schedule included a set snack time in the middle of the morning. After hearing about the benefits of blocks of play, the school switched to an open snack. Kids could eat if they were hungry, but playtime wasn't stopped. What an amazing difference! Suddenly the morning play time transformed. Children got deeply involved with play. Ideas and language skills blossomed. "Thank God we got rid of snack time," one parent said. "So this is what uninterrupted play looks like."

We can do this in our homes, too. Be aware of how many outings and transitions you place in the day. It's fine to go out, but strive to preserve blocks of time in the day.

We all need this. Adults, too. Open time to develop our own ideas.

Do you have big blocks of time? How can you create 1-2 hour blocks so kids can develop sophisticated play?

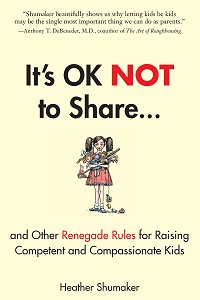

Interested? Learn more about the values of free play in It's OK Not to Share...And Other Renegade Rules.

Interested? Learn more about the values of free play in It's OK Not to Share...And Other Renegade Rules.