A World of Books and Children

Search and enjoy 8 years of posts chock-filled with ideas from It’s OK Not to Share and beyond.

Healthy risk is good. Kids are safer when they know how to cope.

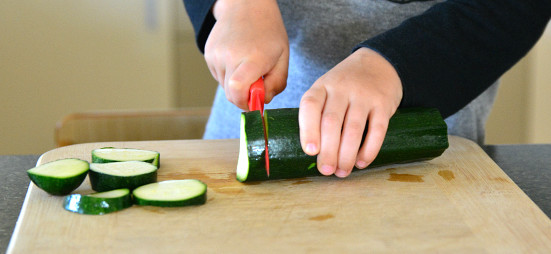

My son burned his finger the other day as he was helping me cook. I love it when these things happen. Not the pain, of course. What I love is when kids engage in real life and learn how to cope.

We'd talked about the pot being hot and using potholders, but still his finger landed on the rim of the hot pot and he jerked it away the way our bodies teach us in an instant. "You burned your finger," I said. "Put it under cold, running water." We turned the tap on.

I'm sure he'll burn his finger slightly again someday. But here's what he won't forget: what to do about it. He'll stick it into cold, running water.

My father used to teach us how to fall. He encouraged us to balance on logs, jump across streams that were too big for us, and go rock hopping, but he prepared us by teaching us what to do when we fell. The assumption is that sometimes you will fall. If you are living. If you are trying. If you are exploring and discovering and engaging.

Instead of sheltering kids from the burn or the fall, teach them what to do when it happens. This is true of any healthy risk we let our kids take, including sad and angry emotions. Learning how to cope with the ouches of life is what kids need. It's a lot more safe than sheltering.

Healthy risks young kids can try -

- cutting with a sharp knife

- using a real hammer and saw

- running too fast on concrete

- climbing

- leaping from rock to rock

- hauling heavy bricks

- handling sharp needles and scissors

- cooking with supervision

- playing alone

- playing outside alone

- walking to the neighbor's to deliver a message

- asking someone to play

- being told no

My new book delves into why we should put Safety Second. We live in a world of "safety first," but safety first doesn't create full human beings. Safety needs to be part of what we do, but when safety edges out healthy life experiences like playing with sticks in the park and using real tools, we need to err on the side of life.

What types of play or experiences have you seen adults ban recently? What risks do you welcome for yourself or children in your life? What healthy risks are you willing to give a try?

Read more about Safety Second and benefits of healthy risk in the new book "It's OK to Go Up the Slide." Read it? REVIEW it on Amazon or Goodreads.

Read more about Safety Second and benefits of healthy risk in the new book "It's OK to Go Up the Slide." Read it? REVIEW it on Amazon or Goodreads.

Treating kids differently does not mean playing favorites.

We don't want to play favorites. That's a basic tenet of raising kids. Yet our quest for impartiality can get in the way of recognizing, supporting or celebrating one child.

Don't play favorites, that's still true, but kids can handle differences. Life does not have to be equal.

The other day I went to a youth presentation and was struck by how well a 12-year-old boy read. He was clear, dramatic and did his part with such poise that I went up to the family afterwards. "Thank you," said his father. "We're so proud of James, and of course, we're proud of Tyler and Nate also, they're great kids, too." He added this in an apologetic rush. This attempt at being equal diminished James' recognition. James was the one who read. James was the one we were talking about. His brothers can cope if they don't occupy the spotlight all the time.

We strive so hard to equal, with our words and with our actions. But kids are different, and sometimes those differences mean it's OK to treat them differently.

This goes for gifts and experiences, too. We don't automatically have to buy a gift for every child just because we have something that uniquely fits another. Kids can handle it if every day isn't exactly equal. It happens at birthdays already. Everyone gets a birthday, but it's not usually the same day. One person gets showered with special attention today, the other one has a turn in a few weeks. The overall balance and value of each individual is what's most important.

If everyone is praised equally and often (see "Stop Saying 'Good Job!'" in the book It's OK Not to Share), it becomes meaningless. Kids don't need constant praise, but they do value genuine interest and observation: "I was really struck by how clearly you read. I could hear every word even in the back." That's recognition. When kids say "That's not fair!" that's an excellent instinct for social justice. "Why does he get to stay up late I have to go to bed now? That's not fair!" Reframe it for kids: "Your body needs more sleep. When Sam was your age he went to bed when you do" (see "Share Unfair History" in the book It's OK to Go Up the Slide).

So support the kids in your life, celebrate their individuality, and support their interests. Sometimes being fair is more valuable than being equal.

What do you think? It's a tricky balance. Meeting an individual's needs --all individuals -- can be what's most important. Have you ever felt stuck in these situations?

NEW BOOK - Read it? Love it? Write a review on Goodreads or Amazon. Order here.

NEW BOOK - Read it? Love it? Write a review on Goodreads or Amazon. Order here.

Speaking up when you don't like something - a great part of kid justice.

What would you say if you saw a group of eight 1st and 2nd grade boys excluding a girl from their running game?

Possibly this: Sexism. Girls discriminated against. Our adult minds leap to what seems obvious. We might sigh and despair: it starts so young, especially in sports. We might speak up and intervene; force the boys to let the girls play.

I witnessed this scene recently while volunteering at my children's school. The kids were playing Red Light Green Light, taking turns to be the stoplight and running up sneakily when his/her back was turned. Except one child - Tessa - didn't play fairly. She made all the boys go out and picked a favorite friend to win over and over and over.

The kids got mad. Then they did all the right things. They told her exactly what they didn't like, they reminded her how to play by the rules, and when she didn't stop they excluded her from the game.

Because I'd seen the whole game from its beginning, I knew exactly why the boys weren't letting Tessa play. It was Justice. Kid justice. Instead of being mean or discriminatory, they were simply standing up for themselves, protecting the game, and putting her in her place. The game wasn't fun when she played it like that.

Kids' actions and game rules do not always look fair to adult eyes. But they may be fair to the children.

Before we barge in, stop and listen, see what's happening. Ask questions if you're worried: "Is that OK with you?" Toys and roles may not be evenly distributed, but they may be right for the game, they may be right for the children involved in work or play.

Our goal shouldn't be that everyone is treated the same. We are not all the same, so being treated the same isn't respectful. Focus instead on helping kids speak up and set limits when they don't like something. That's a courageous act of peace. And sometimes, of justice.

What do you think? Have you witnessed times when adults step in for fairness, with the wrong results?

More about "That's not fair," respect and justice in the new book "It's OK to Go Up the Slide." Got it? Read it? Review it!

More about "That's not fair," respect and justice in the new book "It's OK to Go Up the Slide." Got it? Read it? Review it!