A World of Books and Children

Search and enjoy 8 years of posts chock-filled with ideas from It’s OK Not to Share and beyond.

One of the stops I made on my book tour this summer was Phoenix Books in Burlington, Vermont. There, next to my poster on the bookstore window, was a poster for another parenting book by Vermonter Vicki Hoefle. Vicki and I never met, but I felt a kinship since we shared the same space on Bank St. Not long after, Vicki reached out to introduce herself and her book Duct Tape Parenting.

Vicki’s book is inspiring for how to raise problem-solving, independent kids. In her world, five-year-olds pack their own lunches and get ready in the morning routinely and without complaint. Teenagers pay for their own cell phones and car insurance, not to mention their own cars.

Her motto: “If they can walk, they can work.”

In other words, she believes children are capable beings. She trains them. And trusts them. Vicki herself has five grown kids. This is reality; not fantasy.

Lest you think Vicki’s world is all work and no play, it’s actually fundamentally about respecting feelings and valuing family relationships. Using a base in Adlerian and Dreikus’s psychology, she focuses on seeing the best in our kids and helping them achieve that through a combination of firmness and kindness.

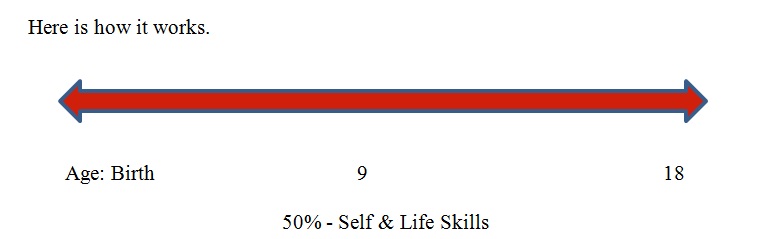

One idea I like is her “Timeline for Training.” This helps us realize how much time we really have to raise our children into competent, independent folks. If our kids know nothing at age 0 and need to know everything – money management, household care, self care, responsibility – by 18, where should they be today? Does your 9-year-old know 50% of the life skills he should know?

Her book is for raising kids of any age – birth to teen. What I like is that she outlines a plan for helping to transform your family, so if you are currently in the do-everything-for-your-child mode, (the “maid”) you can follow her steps to create a new family reality. If your kids aren’t doing what they could do, it’s likely that the relationship needs repair and/or the kids need training.

She shares three optimal windows for training:

Birth to 9 = Life skills and self skills (making beds, remembering gear, doing laundry)

10–15 = Social world skills (making appointments, apologizing, saying no)

16-18 = Real life skills (cooking and menu planning, changing oil, dealing with alcohol)

Vicki's book isn't all about chores. It's about letting kids problem-solve, gain trust and take reasonable risks. For parents, it's about not nagging or reminding, and most of all not rushing in to save them. So if you’re ready (in Vicki’s words) to “Quit your job as a maid,” check out her book and her website. There you can also listen to parenting podcasts and hear the one featuring my book It's OK NOT to Share - (the closest Vicki and I ever got to meeting!).

What tasks do you think your children are capable of doing that they’re not doing? Why do you think we’re reluctant to have kids contribute?

When my grandmother was losing her memory, she still remembered the poetry she had memorized as a girl. She had no idea who I was ("this is my great friend...(pause) tell me again how we met?"), but out for a walk together she would stop and gaze with joy at a tree. From the depths of her memory she would recite:

I think that I shall never see, a poem lovely as a tree...

She was from an era that taught poetry recitation in school. Maybe she picked it up on her own or learned it from her parents, but the point is she had a suite of poetry at her command. Poetry to fit every mood - happy or melancholy.

In this era of INFORMATION, we hardly memorize anything. Need an answer? Pick up the smartphone. Need a poem? Google it. Memorization seems as quaint as a horse and buggy.

Yet I think there's a place for it. One reason to memorize is to meet our human emotions. Words inside, at the ready, for any human occasion - grief, loneliness, silliness, joy. Like lyrics from a song, poetry can meet many moods and burst out of us when we need it. What else should we memorize? Here are some ideas.

Home and family Young kids should memorize their address and phone number, plus their parents' actual names. That's for simple safety. But I also think it's worthwhile for kids to memorize some family heritage. What are their grandparents' names? Where did they come from? What are some important family stories? Family oral history is a strong force which grounds children in their heritage and identity. Kids in some cultures can recite their family history several generations back.

Songs and poems Songs are easy to memorize, but we need to make sure that we don't just stick with "happy" songs. Sing sad songs to kids, sing songs about longings, missing people, feeling lonely, being angry -- the range of human emotion. We're all bound to experience these feelings throughout life. Songs that match our many moods are good life companions. Read poems to kids they might not quite understand, ones that set a mood. Verses we memorize young stay with us.

Language As English speakers, we're cursed with a peculiar language where spelling and pronunciation do not match. Conventional spelling therefore must be memorized -- but not too soon. It's more important to write and read and find joy in literacy. As an author, I'm a big proponent of letting kids write stories and spell any ole which way when they're writing. Memorize spelling on the side and eventually writing and spelling will mesh.

Basic brain tools Knowing the multiplication tables by heart saves time. Sure, we can look it up, but it slows other thinking if we don't know 6x6 instantaneously. The same is true of memorizing key signatures for music students, or other commonly used data.

Of course, we can set out to memorize at any age, but the words, songs and ideas that we memorize when we're young tend to last a lifetime. What should we fill our heads with? What should we fill our children's heads with? What is important enough to require memorization?

What sort of things do you have memorized? Is there a need any more? Do you see value in having kids memorize stories, songs or poems?

I was rather startled to read on several parenting websites that the "standard" allowance these days is considered to be $1 = 1 year of age. Seriously? That means a five-year-old gets to spend $5 per week and a nine-year-old is regularly spending $9 on candy or (more likely) iphone apps.

I can't imagine giving a child that much discretionary income. I rarely spend that much on myself in a month. OK, I realize we live in the far, frozen north, but even adjusted for big city prices, it seems to be a heavy emphasis on buying-buying-buying. I want to teach my children money management, not how to be constant consumers.

First, a few things about allowances.

An allowance is given to teach a child about money. It should be separate from chores. Pitching in at home is part of being a family. It should not be "paid" for. Some families like to offer money for extra big, once-in-awhile tasks as a way for a child to earn some money; that's fine. A regular weekly allowance is intended to allow a child to make decisions on a few age-appropriate purchases.

An allowance should start when a child expresses interest. For some kids, that's early. My brother always wanted to buy trading cards and bubblegum at age 3, so he started young with a dime allowance. When it was gone it was gone. For kids who don't care much about money, anytime in elementary school is a good time to start.

Set an amount that fulfills some of their wishes. Children's movies in our town are 25c. That's unusual, but think about the top 3 small things your child would like to buy. How much do they cost? Set the allowance in that range. Maybe it's enough to buy a special drink once a week, or the price of sheet of stickers. Think small.

Set an amount that requires thinking and restraint. Contrary to the dollar-a-year guidelines, I started my oldest at 25 cents. He goes weeks without spending anything and sometimes has to save up. So far his only spending interests are popcorn and ice cream from the ice cream truck. School popcorn is 25c. Ice cream bars are $1 +. He's decided weekly popcorn isn't a wise use, but saving up for the ice cream truck is.

Don't go overboard with younger siblings. We give my four-year-old a penny. He plays with pennies as toys - rolling them, making them into pirate treasure. No use giving him anymore until he understands the power of buying something and the ability to keep it safe. But he likes his penny - it makes him feel as if he's getting an allowance, just like his big brother.

Impulse control, decision-making, delayed gratification - these are all skills kids can learn (and make mistakes from) with their money. As our kids grow, we'll increase their allowance, but always keep it moderate. I'll write about kids and bank accounts, and ways to learn about big purchases, long-term savings and charitable giving in a future post. Look for it!

What do you think? Is a $1 / age allowance a good idea in today's economy? What do kids spend it on? What kinds of things did you spend your allowance on as a kid? Should we give kids an allowance that exceeds their needs, meets their needs or meets some of their spending needs (wishes)?